On Normative Ethics

Introduction

Within normative ethics--a branch of philosophy concerning theories of "good" behaviour--there are (as yet) two, predominant theories: consequentialism and deontology.

Broadly considered, a consequentialist theory has it that an act is morally good if (and only if) its consequences are morally good. So, in principle, there are an infinite variety of consequentialist theories, which each specify different types of or token consequences as morally good. However, for the sake of this article, we will restrict the consequentialist view to its typical presentation; that is, good consequences are consequences such as to promote "well-being" and/or prevent "suffering"; or, conversely, bad consequences are consequences such as to promote "suffering" and/or prevent "well-being". On the other hand, a standard, deontological theory has it that an act is morally good if (and only if) it comports (in the right way) with a set of normative, behavioural rules. Sharply contrasted with consequentialism, a deontological theory can take an act to be good or bad in virtue of its intrinsic nature; and, the the goodness or badness of that act can obtain over-and-above a conventional, consequentialist analysis. Note that this does not mean that deontological explanations "bottom-out" faster or are less sophisticated than consequentialist ones--one aptly finds a vast literature to the contrary--it is simply that they hold irrespective of an act's consequences, generally considered.

Relevantly, this article offers a brief elaboration on the unsatisfactory nature of adopting either an isolated consequentialist or isolated deontological theory in normative ethics; further, it provides a first approximation towards the promise of "multi-valued" theories, which attempt to unify and refine both consequentialism & deontology.

Main Body

On the unsatifactory nature of the isolated consequentialist & isolated deontological theories, it can be useful to examine their conclusions re hypothetical ethical problems. In particular, since consequentialist & deontological theories have "modal scope"--that is, their postulates hold, not only in the actual world, but across all possible worlds--we can use hypothetical ethical problems to expose the logically necessary (but not necessarily naturally occurring) unsatisfactory claims associated with each theory. This method leads most clearly and directly to the positive account of the article. Consider our first hypothetical problem:

(H1) Mary walks into a hospital. A doctor has two patients who have been attempted murder against and are going to die. It happens that by killing Mary and harvesting her organs, the doctor can save the two patients. Holding other things constant, should the doctor do it?

Entertaining this hypothetical, from the consequentialist theory so described, it's trivially true that the doctor should do it. Observe that the act produces greater well-being against suffering than were it not to be performed; and, subsequent to the act, there is twice as much potential for (more) well-being to manifest in the universe (assuming the patients are fixed to have net-positive lives). Yet, for many (including myself), this is an unsatisfactory ethical conclusion; that is, the doctor should not do it. One may say that Mary's "right" not to be murdered by the doctor is sufficient to override the simple, well-being-against-suffering analysis to the contrary; or that something about the immediate, moral character of the doctor-murder is (self-evidently) wrong; or that it is just the sort-of-thing that one should rule against. But note that these are all (approximately) deontological intuitions. So, according to this reasoning, (H1) is such as to favour against an isolated, consequentialist normative ethical theory (due to its unsatisfactory conclusions), and provide evidence towards its rival theory, deontology.

Of course, preliminary remarks indicate that this reasoning is incomplete--i.e., an isolated deontology must also entail unsatisfactory ethical conclusions. In fact, by introducing our next hypothetical ethical problem (below), one exposes the fact that an isolated deontology poses (literally) infinitely more unsatisfactory ethical conclusions than an isolated consequentialism. Slightly varying our original, hypothetical ethical problem, consider:

(H2) Mary walks into a hospital. A doctor has an infinite number of patients, from infinite universes, who are infinitely sentient, and have been attempted murder against, going to die. It happens that by killing Mary and harvesting her organs, the doctor can save all the patients. Holding other things constant, should the doctor do it?

Needless to say that a normative ethical theory which entails the correct answer to this hypothetical “No,” is one quite less than ideal! And further, this hypothetical should be taken without loss of generality; for in respect of any given action (e.g., doctor-murder) that a deontologist deems bad (rules against), one is permitted to infinitely scale up the well-being-promoting consequences of that action while the deontologist remains logically-glued to its negative moral status. Indeed, the only variant of a deontological theory able to avoid this problem would be such as to take its deontological rules broadly enough to simply become consequentialism; of course, in this case, one is met with the same ethical problem encountered in (H1).

Informally, given considerations re (H1) & (H2), our normative ethical dilemma is this: How do we make compatible (at once) some measure of "narrowness" (for (H1)) and some measure of "calculation" (for (H2)) in our normative ethical theories?

From here, we can introduce our (previously mentioned) "multi-valued" theory. First, let's attempt to summarise more accurately: Using (H1) and (H2), we uncovered a relationship between the satisfactory-ness of our normative ethical theories and the production of well-being against suffering; at (H1), one seeks to insulate Mary’s right not to be murdered by the doctor, and so favours a deontological theory that "absorbs" the net negative consequences associated with the doctor letting the patients die; then, at (H2), applying a limit approaching infinity, we found that the positive consequences of killing Mary can be such as to ineluctably outstrip her rights.

Since we want some form of consistent merger, lets define both a consequential "axiom" and deontological "axiom", corresponding to the fundamental assumption(s) of each theory. We know that if one was to produce a satisfactory theory combining these axioms, it should (minimally) have it that the goodness of an act co-vary (in some way) with the magnitude of well-being against suffering it produces. However, we also know that including a rules-/rights-based axiom in the theory prohibits a directly proportional relationship borne therebetween.

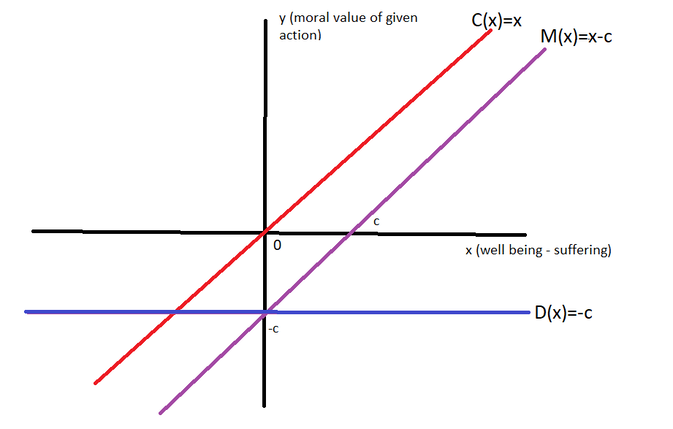

So, we want some sort of constant, deontological consideration that "pulls back" on a variable (potentially overriding) moral force of consequentialism. Accordingly, it is appropriate to represent the behaviour of our axioms, and resulting "multi-valued" theory, graphically[i]. This should be the concluding representation of our positive account.

Let D(x) be a function which represents a deontological axiom

Let C(x) be a function which represents a consequentialist axiom

Let M(x) be a function which represents the multi-valued theory

Let c = some arbitrary, positive constant

Hypothesis: An act is good if (and only if) it exists for some M(x)>0

Introduction

Within normative ethics--a branch of philosophy concerning theories of "good" behaviour--there are (as yet) two, predominant theories: consequentialism and deontology.

Broadly considered, a consequentialist theory has it that an act is morally good if (and only if) its consequences are morally good. So, in principle, there are an infinite variety of consequentialist theories, which each specify different types of or token consequences as morally good. However, for the sake of this article, we will restrict the consequentialist view to its typical presentation; that is, good consequences are consequences such as to promote "well-being" and/or prevent "suffering"; or, conversely, bad consequences are consequences such as to promote "suffering" and/or prevent "well-being". On the other hand, a standard, deontological theory has it that an act is morally good if (and only if) it comports (in the right way) with a set of normative, behavioural rules. Sharply contrasted with consequentialism, a deontological theory can take an act to be good or bad in virtue of its intrinsic nature; and, the the goodness or badness of that act can obtain over-and-above a conventional, consequentialist analysis. Note that this does not mean that deontological explanations "bottom-out" faster or are less sophisticated than consequentialist ones--one aptly finds a vast literature to the contrary--it is simply that they hold irrespective of an act's consequences, generally considered.

Relevantly, this article offers a brief elaboration on the unsatisfactory nature of adopting either an isolated consequentialist or isolated deontological theory in normative ethics; further, it provides a first approximation towards the promise of "multi-valued" theories, which attempt to unify and refine both consequentialism & deontology.

Main Body

On the unsatifactory nature of the isolated consequentialist & isolated deontological theories, it can be useful to examine their conclusions re hypothetical ethical problems. In particular, since consequentialist & deontological theories have "modal scope"--that is, their postulates hold, not only in the actual world, but across all possible worlds--we can use hypothetical ethical problems to expose the logically necessary (but not necessarily naturally occurring) unsatisfactory claims associated with each theory. This method leads most clearly and directly to the positive account of the article. Consider our first hypothetical problem:

(H1) Mary walks into a hospital. A doctor has two patients who have been attempted murder against and are going to die. It happens that by killing Mary and harvesting her organs, the doctor can save the two patients. Holding other things constant, should the doctor do it?

Entertaining this hypothetical, from the consequentialist theory so described, it's trivially true that the doctor should do it. Observe that the act produces greater well-being against suffering than were it not to be performed; and, subsequent to the act, there is twice as much potential for (more) well-being to manifest in the universe (assuming the patients are fixed to have net-positive lives). Yet, for many (including myself), this is an unsatisfactory ethical conclusion; that is, the doctor should not do it. One may say that Mary's "right" not to be murdered by the doctor is sufficient to override the simple, well-being-against-suffering analysis to the contrary; or that something about the immediate, moral character of the doctor-murder is (self-evidently) wrong; or that it is just the sort-of-thing that one should rule against. But note that these are all (approximately) deontological intuitions. So, according to this reasoning, (H1) is such as to favour against an isolated, consequentialist normative ethical theory (due to its unsatisfactory conclusions), and provide evidence towards its rival theory, deontology.

Of course, preliminary remarks indicate that this reasoning is incomplete--i.e., an isolated deontology must also entail unsatisfactory ethical conclusions. In fact, by introducing our next hypothetical ethical problem (below), one exposes the fact that an isolated deontology poses (literally) infinitely more unsatisfactory ethical conclusions than an isolated consequentialism. Slightly varying our original, hypothetical ethical problem, consider:

(H2) Mary walks into a hospital. A doctor has an infinite number of patients, from infinite universes, who are infinitely sentient, and have been attempted murder against, going to die. It happens that by killing Mary and harvesting her organs, the doctor can save all the patients. Holding other things constant, should the doctor do it?

Needless to say that a normative ethical theory which entails the correct answer to this hypothetical “No,” is one quite less than ideal! And further, this hypothetical should be taken without loss of generality; for in respect of any given action (e.g., doctor-murder) that a deontologist deems bad (rules against), one is permitted to infinitely scale up the well-being-promoting consequences of that action while the deontologist remains logically-glued to its negative moral status. Indeed, the only variant of a deontological theory able to avoid this problem would be such as to take its deontological rules broadly enough to simply become consequentialism; of course, in this case, one is met with the same ethical problem encountered in (H1).

Informally, given considerations re (H1) & (H2), our normative ethical dilemma is this: How do we make compatible (at once) some measure of "narrowness" (for (H1)) and some measure of "calculation" (for (H2)) in our normative ethical theories?

From here, we can introduce our (previously mentioned) "multi-valued" theory. First, let's attempt to summarise more accurately: Using (H1) and (H2), we uncovered a relationship between the satisfactory-ness of our normative ethical theories and the production of well-being against suffering; at (H1), one seeks to insulate Mary’s right not to be murdered by the doctor, and so favours a deontological theory that "absorbs" the net negative consequences associated with the doctor letting the patients die; then, at (H2), applying a limit approaching infinity, we found that the positive consequences of killing Mary can be such as to ineluctably outstrip her rights.

Since we want some form of consistent merger, lets define both a consequential "axiom" and deontological "axiom", corresponding to the fundamental assumption(s) of each theory. We know that if one was to produce a satisfactory theory combining these axioms, it should (minimally) have it that the goodness of an act co-vary (in some way) with the magnitude of well-being against suffering it produces. However, we also know that including a rules-/rights-based axiom in the theory prohibits a directly proportional relationship borne therebetween.

So, we want some sort of constant, deontological consideration that "pulls back" on a variable (potentially overriding) moral force of consequentialism. Accordingly, it is appropriate to represent the behaviour of our axioms, and resulting "multi-valued" theory, graphically[i]. This should be the concluding representation of our positive account.

Let D(x) be a function which represents a deontological axiom

Let C(x) be a function which represents a consequentialist axiom

Let M(x) be a function which represents the multi-valued theory

Let c = some arbitrary, positive constant

Hypothesis: An act is good if (and only if) it exists for some M(x)>0

[i] Note that this graph is strictly credited to "Dr. Avi", YouTube = https://www.youtube.com/user/Iwanthax?sub_confirmation=1, first to map-out graphically the consequentialism-deontology synthesis.